De AIVD heeft vandaag op zijn website een Engelstalige verklaring over het afluisteren van telecommunicatie gepubliceerd.

Interception of telecommunications by the AIVD: rules and regulationsEn opnieuw wordt het afluisteren gebagatelliseerd door te benadrukken dat het vooral om metagegevens gaat:

The interception of telecommunications by secret services is surrounded by myths and misunderstandings. What is interception according to the Dutch intelligence services and what kinds of interception do we define? What does the law say? By whom and how are the Dutch intelligence services supervised?

Content and metadataVorige week beschreef Slate, op basis van een verklaring van professor Felton van Princeton hoeveel die onschuldige metadata kunnen onthullen. De voorbeelden zijn redelijk Amerikaans, maar toch:

Telecommunications consist of the message (content) and all the data added for the purpose of transport (metadata), such as a telephone number, an IP number, an email address or location data.

Intercepting telecommunications first and foremost means collecting metadata. Metadata is less substantial in size and can be analysed more quickly. In addition, gathering metadata is a less serious privacy infringement. Analysis of the metadata shows whether the matching content of traffic may be relevant for AIVD investigations.

Most data is irrelevant for AIVD investigations. If, based on a carefully designed assessment trajectory, the data does prove to be important, the Minister of the Interior and Kingdom Relations must be asked for permission to also look at the content.

NSA collection of our metadata means the government knows when we’ve called a rape hotline, a domestic violence hotline, an addiction hotline, or a support line for gay teens. Hotlines for whistleblowers in every agency are fair game, as are police hotlines for “anonymous” reports of crimes. Charities that make it possible to text a donation to a particular cause (say, Planned Parenthood) or political candidate or super PAC could reveal an enormous amount about our political activities. And calling patterns can reveal our religious beliefs (no calls on Sabbath? Heaps of calls on Christmas?) or new medical conditions. If, for instance, the government knows that, within an hour, we called an HIV testing service, then our doctor, and then our health insurance company, they may not “know” what was discussed, but anyone with common sense—even a government official—could probably figure it out.En als Target op basis van allerlei aankopen voorspellingen kan doen, dan kan de regering vast ook wel het een en ander afleiden hè.

But there’s more, says Felten: By analyzing our metadata over time, the government can separate the signal from the noise and use it to identify behavioral patterns. The government can determine whether someone is making lots of late-night calls to someone who isn’t his spouse, for example. When those calls cease, the government might reasonably conclude that the affair has ended. Metadata may reveal whether and how often someone calls her bookie or the American Civil Liberties Union or a defense attorney. And by analyzing the metadata of every American across a span of years, the NSA could learn almost as much about our health, our habits, our politics, and our relationships as it could by eavesdropping on our calls. It’s not the same thing, but the more data the government collects, the more the distinction between metadata and actual content disappears.

De PreCogs komen er aan en ze gebruiken big data...

Gerelateerd

Hoe de supermarkt weet wat je nodig hebt

Het waren slechts metadata

Dat metadata niet zo onschuldig zijn...

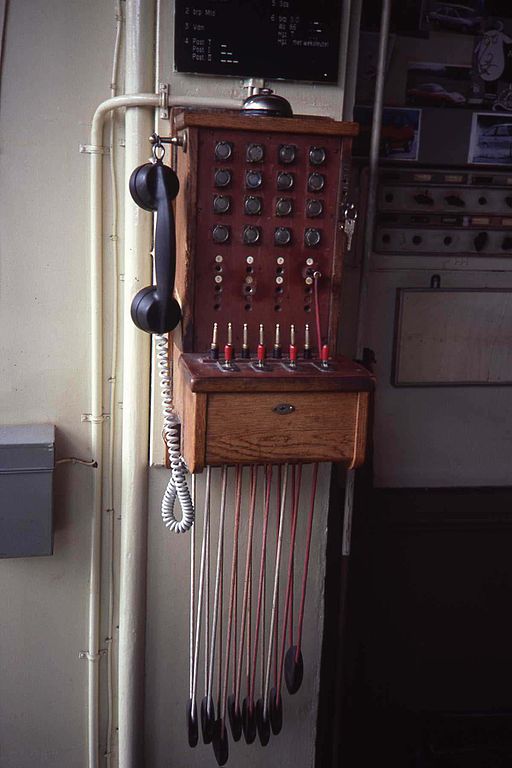

Plaatje:By Smiley.toerist (Own work) [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten